Games Studies

Contextual Research

Task One - Computer Game Studies, Year One

We were asked to write a short response to http://www.gamestudies.org/0101/editorial.html by Espen Aarseth as our first research into games as a field of study. Here are a few of my thoughts:

Aarseth talks about how games combine aesthetic and social aspects in a way that previous mass medias have failed, creating entirely different requirements from an audience for a game to 'work'. Participants need not interact with one another when it comes to old mass media, only with the medium itself. Multiplayer games are almost the opposite of this, where communication is key. As the article states, this balanced combination of facets presented in digital games has greatly innovated audience structure.

They explain that to consider games as a 're-invention of Hollywood' would be to ignore the socio-aesthetic qualities of digital games and project out of date ideologies on to a new medium, however then goes on to compare Nintendo with Hollywood.

Nintendo does have a huge grip on the games market due to their intellectual property being the most popular media franchises in existence, however this doesn't prevent the popularity of inexpensive indie games found on Steam for £0.50.

It is discussed that games can't be watched, read or listened to like other mediums can; they must be played, and active participation is necessary for the very structure of a game. With this considered, it can be argued that games are the only mass media that does more than just 'exist', where it doesn't matter whether an audience is present or not. For a game to reach completion, an active player must be engaged.

Later in the article, Aarseth considers who games studies really belongs to, if anyone, and how each existing field comments on it readily with their pre-existing paradigms, ignoring many of the unique,key aspects that make up a game. Varying scholars from different backgrounds fail to see the numerous and diverse differences between their own field and games studies, which is realistically an entirely unique genre of media in itself.

The quote-

"We have a billion dollar industry with almost no basic research".

shows contrast in how much information was publicly available on the work of authors and directors in comparison to data on games developers. Could this be why studios can come out with four amazing titles in a row only to release an absolute flop the following year?

Full version on 'Further Research' page.

Glossary:

- Paradigm: noun

-

a framework containing the basic assumptions, ways of thinking,and methodology that are commonly accepted by members of a scientific community.

-

such a cognitive framework shared by members of any discipline or group:

the company’s business paradigm.

- Integral: adjective

1. of, relating to, or belonging as a part of the whole; constituent or component:

integral parts.

2. necessary to the completeness of the whole:

Task Two - Serious Games: Pokemon Go

We were asked to play what we considered to be a 'serious game' and write about it's ability to persuade and other responses.

I view Pokemon Go as a form of 'serious game' purely due to the results that come from playing.

The app managed to persuade millions of users to walk long distances everyday without much question because the Pokemon they catch as a result are deemed 'worth it'.

It's also interesting how the game's premise is to capture and battle creatures for sport to the point of passing out, even though this is illegal in numerous countries. The visual presentation of the Pokemon makes it seem okay to players because they're cute, colourful and can't technically 'die', so many people never give this a second thought.

The game isn't necessarily 'fun' in comparison to a game like Super Smash Bros, as you have to walk for miles to achieve anything whilst draining your device battery and occasionally catching the same Pokemon you caught 50 times previously that same day. However, the app convinces the player that they're having fun through their reward system, providing a great level of satisfaction when provided with prizes and gifts for their basic accomplishment of flicking an imaginary sphere on their phone.

The social context of the app pushes it's users to strive to be better than their friends and peers through a levelling system and three coloured teams, splitting players into factions before they've even started any level of game-play. Pitting players against each other creates sportsmanlike rivalry and urges them to complete more gym battles and catch more Pokemon and even put real money in to the app for extra rewards and goodies.

The fact that this game get's players to exercise in real life, battle animals for sport and fight against their friends is all down to it's visual design, reward system and social context.

Niantic 2016, Pokemon Go, Mobile App, iOS/Android, Niantic, California.

Task Three - Game-play Experience and Flow: The Stanley Parable

We were asked to write about our own game-play experience that invoked flow and relate them to Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi's conditions on how to achieve flow.

The game I feel puts me into the greatest state of 'flow' is The Stanley Parable.

In terms of Csikszentmihalyi's conditions, the game is immediately suitable for me in that the mechanics are extremely basic, so I know that nothing can get overly challenging or stressful; this relates to his conditions of knowing that the activity is do-able and a sense of serenity as there are no spikes in skill requirement throughout the game, I consistently feel that I know what I'm doing.

The Narrator in The Stanley Parable provides the sense of being out of the ordinary, an expressive voice that is dictating Stanley's every movement. The 'sense of ecstasy' is achieved through the one-sided altercation between the player and narrator, almost like a battle of conscience out loud.

For me, greater inner clarity comes in the form of choice as a player. Knowing that I can control the game for an outcome that I want by ignoring the narrator it becomes my goal to defy everything he says, and he helpfully confirms how far I have strayed from the main path as his comments become more apathetic and dry.

When it comes to timelessness this game completely swallows me whole; I've played approximately 12 hours regardless of the total game-play only being 2 hours with one run-through. I completely lose track of time as I try to remember what endings I had discovered previously, which paths lead to which results whilst still being surprised by small things that happen at random during the Nth number of play-throughs.

The varying choices and biting humour engage me more as a player than any amount of action or violence ever could, and make what would otherwise be quite a monotonous game into a humble masterpiece.

Galactic Cafe 2013, The Stanley Parable, Video Game, Microsoft Windows/Mac OS/Linux OS, Galactic Cafe, U.S.

Games based on Warhammer's rules and mechanics:

- Warhammer Ancient Battles

- Warhammer 40k

- Blood Bowl

- Mordheim

- Warhammer Fantasy Roleplay

- Dark Heresy

- Judge Dredd: The RPG

- Inquisitor

Games based on Warhammer's setting:

- Warmaster

- Chaos Marauders

- Numerous games released by Games Workshop

Task Three A - Pre-Digital: Warhammer: The Game of Fantasy Battles

I know that Warhammer came out during the Golden Age of arcade games, however it's relevance in terms of non-digital games is strong in the history of play.

Originally released as 'Warhammer Fantasy Battle' in 1983, Warhammer is a table-top war game created by Games Workshop in England.

Various editions have been released over the years, with the ultimate 8th edition being the last in 2010.

The players can choose from different races of armies, including humans, elves, dwarves, lizardmen, orcs etc. that a represented by a collection of paintable miniatures referred to as a 'unit'. The strategy game was designed to simulate war in an organised manner, following rules presented in each edition's books.

Movement and combat are dictated by the rolling of two D6 dice, one movement die and one artillery die.

Warhammer created a fictional universe based on Michael Moorcock's stories and varying historical influences. It's geography is based on that of Earth and was inspired by Reaper, a similar game that simulated small skirmishes rather than all-out war.

The first edition consisted of three books, each explaining different aspects of game-play. Not much world or character lore is provided in this edition, but it was enough to create the foundation of a table-top game that would last almost thirty years.

On release, the game was deemed inconsistent in it's initial rules and failed to produce adequate presentation. Regardless of this, it was the battle system that proved to be superior in comparison to similar games. This is what made Warhammer stand out and envelop the market for table-top war simulation games.

It The psychology behind how different fantastical races would interact with one another in tandem with the use of magic gave the game a stronger, more believable fantasy environment. The world of Warhammer grew massively with the release of sci-version Warhammer 40k and Games Workshop currently has approximately 400 physical stores in the UK. There are no modern competitors to Warhammer due to it's complete domination of it's niche market.

https://cf.geekdo-images.com/opengraph/img/M9KO_R8XSNjsLNw42yzMujSgArI=/fit-in/1200x630/pic52670.jpg

There have been a few video games that incorporate very similar battle mechanics and rules over the years, the biggest and most obvious being the Total War Franchise. Nearly all of the games in this series feel like digital versions of Warhammer matches, only using historical figures rather than lizardmen. Many war games will include something from the Warhammer system, like in Stellaris and many other real time strategy video games.

In terms of Ian Bogost's thoughts on the power of words, Warhammer manages to trivialise the monstrosity that is war and puts a positive and competitive outlook on it, taking words like 'domination' and 'invasion' and making them something to admire and attain, rather than avoid like people would naturally in normal life.

The power of the different races and abilities to conquer are seen as desirable traits through the miniatures impressive design and visible passion and loyalty to fight for their army.

In addition, the physical design of the different factions clearly create a divide between who is to be deemed as 'good' or 'bad', using blacks, reds, horns, dirty armour and pointed teeth on Chaos miniatures whilst Wood Elves have an ethereal look, using lighter colours and natural themes like antlers and crystals. The two designs are extremely contrasting which creates interesting visual conflict on a Warhammer table.

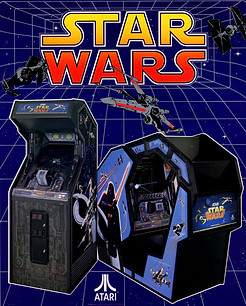

Task Three A - Arcade Era: Star Wars

Atari released the Star Wars arcade game in 1983 (the same year that Warhammer was first released) during the Golden Age of arcade games. It utilises 3D colour vector graphics and was found in both upright cabinets and sit-down cockpits.

The player takes the role of Luke Skywalker as he pilots the signature X-wing space craft, dodging enemy attacks and firing their own.

This was one of the first games that allowed the player to complete the game by survival rather than having to defeat every single enemy, like Space Invaders. The player starts with six shields and only needs to survive to continue on to the next round.

There are three attack phases which, when completed, restart and get gradually more difficult by increasing speed and adding more enemies.

It also incorporates digitised sound samples directly from the original movie. Physically, the arcade units are covered in decals with art depicting classic characters such as Darth Vader. The controls included a yoke wheel and four buttons, layed out as two triggers behind either side of the yoke.

Development started in 1981, initially titles 'Warp Speed' and the team was lead by Ed Rotberg. Rotberg left Atari later that same year, so Atari signed a licensing agreement with Lucasfilm and completed the development as Star Wars: The Arcade Game.

In 1983 and 1984 the Parker Brothers converted the game from arcade for several 8-bit consoles and computers including Atari 2600, 5200 and Commodore 64.

In 1987 and 1988 Vektor Grafix converted the same game again, only this time for Amiga, Atari ST, ZX Spectrum and some others. Within the same year Broderbund gained their own Lucasfilm licensing and published versions of the game for Apple ll, Macintosh, Commodore 64 and MS-DOS.

Out of all of these conversions, the most alike the original were for the Amiga and Atari ST.

Atari produced 12,695 units, making Star Wars:The Arcade Game one of the best selling games of 1983. It was given 3/5 stars in Dragon #145 whilst Compute! described it as "amazing, smoothly animated". It was listed as one of the 'Top 100 Games of All Time' by Next Generation in 1996 and in the 'Top 100 Arcade Games of All Time' by Killer List of Videogames website.

As it was one of the few games to a vector display during the Golden Age it meant that colour and detail were sacrified to prevent pixelation. It suited the first-person perspective of the game but occasionally made it difficult to understand depth on screen.

It was one of the very first video games to be created based on an existing movie, second only to Tron. It was an early look in to how Lucasfilm would branch out with it's licensing for a whole world of merchandise and entertainment, some of which is considered priceless today.

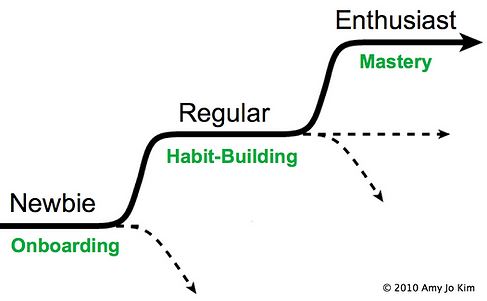

By being one of the first games to be about survival rather than completion it cleared a path for games that were more accessible for entry-level gamers, rather than being 'gamer' exclusive. As the game increased in difficulty after every clear run-through it was still appealing to more enthusiastic players, allowing them to strive towards higher scores and longer survival times. This makes it a game that was easier to play, but harder to master. Players with greater skill would likely achieve 'flow' in the early levels as it would be easy enough to not be stressful, yet still utilises their abilities.

In terms of a player's journey, coined by Amy Jo Kim, it allowed players to easily discover the game and get on board without the need to master the game as they didn't need to destroy every single enemy, something that previous games had failed to achieve.

Atari 1983, Atari, Star Wars: The Arcade Game, Arcade Game, Atari, U.S.

Tron 1982, Bally Midway, Tron, Arcade Game, Bally Midway, U.S.

Task Three A - Contemporary: Pokemon Go

I've written about Pokemon Go vaguely in the task about playing a 'serious game', however this lead me to think about how it could be written about in terms of it's power of persuasion and existing franchise in comparison to the other chosen games.

Pokemon Go is a free-to-play/location based/augmented reality mobile app developed by Niantic for iOS and Android released in 2016. A collaboration of Niantic, Nintendo and The Pokemon Company was required for licensing and development.

It utilises the device's GPS capabilities, allowing the player to locate, track, capture, train, evolve and battle Pokemon that can be found as a player walks along. The augmented reality setting can be toggled, presenting the pokemon as if they are in front of the player in real life by using the device's main camera.

The game also includes in-app purchases for additional game items, making it a freemium service (a business model, where basic services are provided for free while more advanced features must be paid for).

Pokemon is a media franchise founded in 1995, it's main premise being that players can capture fictional creatures called 'Pokemon' and battle others to train and increase in power. It's owned by The Pokemon Company, an association shared between Nintendo, Game Freak and Creatures. The franchise is co-owned, however Nintendo individually hold the trademark rights.

It's one of the best-selling game franchises, second only to the Mario franchise owned by Nintendo. Pokemon is however the highest-grossing media franchise of all time, with over 300 million copies of the varying Pokemon games being sold over the years.

Go was released 20 years after the first Pokemon games were released, Pocket Monsters Red & Green.

On first release the game experienced fluxuating technical issues in varying countries, however this wouldn't stop it from being downloaded over 500 million times across the world by the end of 2016. Due to this incredible global interest, it became one of the most used apps of the year, leading to a 9 billion dollar market value increase within the first five days of the app's release and a 50% increase in Nintendo's share pricing by mid July 2016. By late July, Nintendo's stock had risen above 50% compared to pre-app release. However once it became clear that Nintendo didn't develop the app nor gained financially from it, the stock decreased by 18% once more.

The immediate interest in Nintendo, rather than the developers or the other joint owners, from investors was due to their larger influence and assumption that it was entirely their intellectual property.

In July of 2016 over 230 million people had been involved in 1.1 billion different interactions on Facebook and Instagram involving Pokemon Go in one way or another. Press of all mediums, including television news, were talking about the app's phenomenal popularity, resurfacing the term "Pokemania" which was used by media outlets like Time magazine in the 90s during the franchise's earlier years of success.

People from differeing cities worldwide were catching Pokemon, gathering at Pokestops (digital in-app pin points that provided free in-game content, commonly located at landmarks or shops) and was the first video game to promote players to go outside, become active and communicate with one another face-to-face in the real world.

During one of the many updates, Niantic introduced an option to choose one Pokemon as a "buddy", where the more steps the player took the more rewards they would receive for their chosen buddy. This, along with the main features of the app, hugely encouraged physical exercise and had players of all ages out and dynamic, something no other games had ever achieved previously on such a substantial scale.

Pokestops also resulted in several positive outcomes: swarms of people would turn up in specific locations where strangers would often interact with each other about their common interest of catching pokemon. This strange fluxuation in the public's movement increased business for those located near or as Pokestops, regardless of how popular they had been previously. Many of the stops were located at historical landmarks too, with descriptions of the locations being added in updates, it aided in the education of local history.

The crowds drawn in by the app also allowed players to safely report crimes as they occurred, for example there were two players in Fullerton, California, who aided in the capture of a man wanted by police for multiple crimes whilst they were using the app [1].

The gender-fluid community praised the app for allowing the player to pick a 'style' rather than a 'gender' and Pokemon came as either male, female or genderless [2].

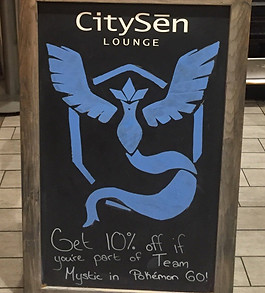

Many local businesses put up signs detailing discounts available to players based on their team choice of obtainment of specific Pokemon, really spreading the 'Pokemania' through the streets.

With this in mind, it can easily be argued that Pokemon Go is a 'serious game' by Ian Bogost's[3] standards as it goes beyond entertainment, with many positive results; even though it includes very basic active game-play it ended up with such powerful and impressive outcomes.

The app captivates users at face-value and persuades players to repeat tasks, drain their device battery and spend real money on in-game items that don't really exist, whether it's upgrades or visual customisation, without a second thought. Go managed to convince millions of people to exercise without explicitly telling them to do so; the psychology behind this is so deep seated the app users don't often realise the positive affect the game has on their daily health routine. (I personally walked an average of three miles more everyday when most actively using the app).

Bogost also said

"You don't have to like games to want a piece of it".

Many people who downloaded and partook in app activities neither played games previously nor knew what Pokemon even was. Parents loved getting involved with this new curiosity for exploration that was planted in young children (my own parents had a great time competing with each other to catch the most basic of Pokemon). Young adults and teenagers didn't want to miss out on the 'hype' even if they didn't like Pokemon and this created a friendly competition for young people at school and at work regardless of existing interests.

Niantic 2016, Pokemon Go, Mobile App, iOS/Android, Niantic, California.

Game Freak 1996, Pocket Monsters Red & Green, Video Game, Game Boy, Nintendo, Japan.

[1] finance.yahoo.com/news/pokemon-blamed-crimes-aids-embattlement-004344471.html

[2] independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/pokemon-go-praised-by-gamers-for-introducing-gender-fluid-avatars-characters-players-lgbt-style-a7132536.html

[3] BOGOST, I. (2007). Persuasive games: the expressive power of videogames. Cambridge, MA, MIT Press.

Task Four - Potential Essay Subjects

We were asked to create a list of potential points to cover in a very short essay plan for each essay theme:

Persuasion

Ian Bogost

- "You don't have to like games to want a piece of it"

- 'Serious Games'

Applied to Pokemon Go

-

how it persuaded people to exercise, making it a 'serious game'

-

had people who didn't game or know what Pokemon was playing

Chris Filip

- Games as propaganda

Applied to Pokemon Go

-

game fails to explain any negatives of battling animals for sport

Applied to Warhammer

-

character design uses semiotics to represent 'good' and 'bad' armies

-

glorifies war and invasion through buzz words like 'domination' and 'ruler'

Immersion

Mihaly Csikszentmihaly

- The state of 'flow'

Applied to Pokemon Go

-

not too difficult so gets many non-gamer users into a state of flow to match their skill level

-

HUD design shows how well they're doing

-

non-violent with simple mechanics, making it stress-free

Applied to Star Wars

-

increases in difficulty, making it suitable for players of multiple skill levels

-

easy to play, hard to master

-

sit-down cockpit and yoke wheel furthers physical immersion

Applied to Warhammer

-

players become invested in the lore

-

psychology of race interaction makes players really invest in the situation

-

timelessness - matches can last hours

Transmedia

Henry Jenkins

- 7 key characteristics of transmedia storytelling

Applied to Pokemon GO

-

already based on long running media franchise

-

continues themes from original games and show in new formats

-

applies existing world onto real world

-

now allows audience to be physically active participants - performance

Applied to Star Wars

-

based on existing piece of media

-

creates performance as players are now active audience members rather than static viewers

-

subjectivity - specifically played from the view point of Luke Skywalker

-

continues characters and themes from the existing movie

Applied to Warhammer

-

drillability - the world its entirely fictional

-

each new version builds upon the world and it's lore

-

subjectivity - different races and their ideologies

Task Five - Experiential Narrative in Game Environments

We were asked to create a short response for Gordon Calleja's article on Experiential Narrative in Game Environments:

Early in the article, Calleja expresses the need to define what kinds of games to discuss when creating a narrative framework, due to the over-generalisation that often occurs when studying games. It would be pointless to discuss the narrative of solitaire with that of The Last of Us when, realistically, these are two vastly different media products, entailing varying differences in appearance, mechanics and player engagement. This would also be problematic, creating a vague, possibly incomprehensible, framework too broad to apply to an one game.

Calleja explains how Zimmeman and Salen take narratives as a given in their work; it can be argued that there is a form of narrative in a game of Solitaire, however I disagree in terms of 'true narrative', as this would ignore several integral aspects of these frameworks. 'True narrative' is what I am describing as narrative in which the player is actively aware of, and engaged with, resulting in their reflection and understanding of the story, whether emergent or embedded.

The idea of 'entity' within games is discussed, with the shift between playing as oneself, like in first person games, and playing as an existing character or miniature. Callega demonstrates how first person games like Mirror's Edge create 'the alterbiography of self', where the players interact with the game environment and characters as if it were actually them, making first person a way of influencing narrative on to the player as 'me' or 'I'. Third person perspectives are a visible character that the player can see that they are in control of, but do not have the connection with the environment as themselves, but rather 'them' or the character name. This can result in a greater involvement with a character's story, no matter how wild it is, because they would never have to be them directly; I feel this would work best for linear narratives as branched narratives within third person can encourage a player to make decisions as that character rather than what path they would actually like to choose.